by Emily Rose Hennings

France was lost by a woman, and will be saved by a virgin." This old prophecy ran fresh in everyoneís mind as news spread that a young maiden was leading the army of France to raise the siege of Orleans. The first part of the prophecy had already come true. Queen Isabella had disinherited her son the Dauphin Charles, the true French King, and had allied with the English. The virgin who was to raise the siege was Joan of Arc.

Around the age of 16, Joan had convinced her cousin, whom she called uncle, to take her to see Robert de Baudricourt, Captain of the Fortress at Vaucouleurs. Her voices had told her that he would give her men-at-arms to go and see the Dauphin in Chinon. When asked what Lord had sent her Joan replied that he was the "King of Heaven" and that it was his will that the English be driven out of France, and that she would lead the Dauphin to be crowned King of France at Reims. The astounded Baudricourt ordered Joan home. Joan returned three times to see Robert de Baudricourt and was denied the men each time. On the third time Joan stormed in and shouted, "In Godís name, you have done wrong in not sending me! This very day, near Orleans, a great disaster has taken placeÖ" Yet again she was denied for Baudricourt had heard of no such battle. Not many days later a priest was sent to get Joan, for news had reach Vaucouleurs a battle had taken place in which the French were forced to retreat, on the very day that Joan had predicted it. This battle is known as the Battle of the Herrings.

Joan changed her peasant dress for a tunic and trousers to prepare for the long journey ahead. Baudricourt sent her off in late February with six men saying, "Go, and come what may."

The journey of 350 miles from Vaucouleurs to Chinon took Joan and her men about eleven days. She entered Chinon on Laetare Sunday, March 6, 1429. The next day Joan was summoned to see the Dauphin. To test her, the Dauphin traded places with the Count of Clermount. When Joan was presented to Clermount as the Dauphin she is reported to have said, "that is not he. I will recognize him when I see him." She walked around the chamber stopping in front of the fireplace where she took off her cap and knelt down before the 26-year-old French Dauphin. Charles asked her who she was and why she had come. She replied that she was known as "Joan the Maid" and was sent by God to raise the siege of Orleans, crown him king, and drive the English out of France. When he asked for proof, Joan took him aside and told him in secret enough to make him believe.

Now that Charles was convinced that she was indeed sent by God, but the clergy still needed proof, so they sent her to Poitiers where she was investigated by theologians to determine if she was sent by God or the Devil.

When asked if God wanted the people of France delivered, then why was there a need for soldiers to fight? Joan replied, "In Gods name, the soldiers will fight and God will give the victory." The scholars were impressed with her clarity, honesty and fearlessness, so it was decided that she was to be sent to Orleans "Öin due state trusting to God."

When preparing to leave the Dauphin offered her a fine sword, she refused it saying her voices had told her of a sword buried behind the alter in the Church of St. Catherine at Fierbois, the sword would be recognized by the five crosses it bore. The monks didnít know of any sword, but looked anyway and sure enough in a niche behind the alter was a rusty sword with five crosses. The rust fell away as the monks began to clean it, it was considered a miracle.

Joan as a soldier

As Joan and her growing military force marched toward Orleans, they gathered well-trained knights like La Hire, the "Angry One," and many others joined her despite their skepticism. She also attracted townsmen and farmers, for Joan had become a symbol of hope, and hope was something that France had not had for as long as anyone could remember.

When Joan arrived at Orleans, she insisted that if the English would not surrender, the city should be stormed and returned to French hands. The English refused to surrender to Joanís many letters, and so the attack began. After days of small skirmishes, Joan rallied the men and in a great push they broke the English force and took Orleans by way of the bridge. Although Joan always rode in the front lines of battle, she never killed a man.

The only picture of Joan ever dawn in her life

Joan had completed the first of the three tasks God summoned her to do, now she was moving on to the second: to see the Dauphin crowned at Rheims.

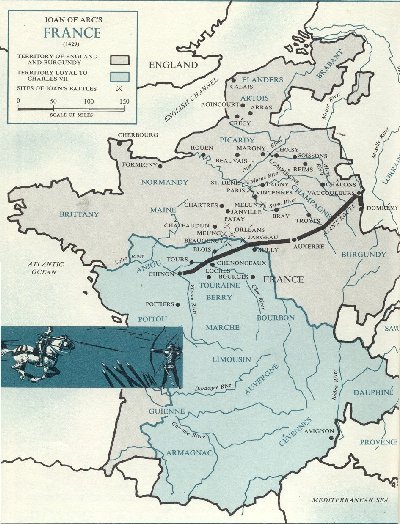

Rheims, unfortunately at that time, was under the control of the English, so Joan set out to take it back. Along the way to Rheims one English stronghold after another fell to Joan the Maid. Jargeau, Meung, Beaugency, Auxerre, and Troyes all fell, although some surrendered and others had to be seized, but none held out longer than two days. This great march from Gien to Rheims is now called the "Bloodless March" and is regarded as one of her greatest military accomplishments. To the English Joan didnít represent hope, she was a witch who had the power to inspire the defeated French army onto victory. When the Maid reached Reims the Burgundians, allies of the English, would not surrender and were prepared to fight, but the people refused and the Burgundians were forced to leave. Joan following behind the Dauphin Charles, entered Reims on March 16, 1429, without a fight.

Map of Joanís France and her battles

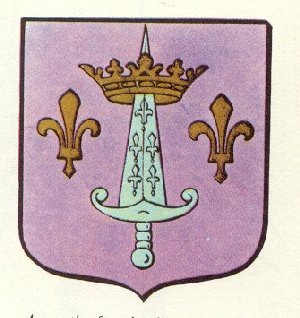

At 9:00 the next morning the Dauphin became King Charles VII of France. Joan stood by his side at the coronation holding her unfurled battle flag, was he was anointed with the Holy Oil and crowned King of France. When Joan was asked why her banner had been used at the ceremony, she answered, "It had borne the burden, it deserved the honor." In honor of her services the King granted Joan the status of nobility and asked her what other gift he could give. She asked simply that her home village of Domremy be granted freedom from taxes. France honored this request for over 360 years, up until the turmoil of the French Revolution when it was forgotten.

Joanís coat of arms

Joan was now on the third task set before her; to drive the English out of France. Joan wanted to capture Paris, she felt with Paris once again under French rule the English would have a hard time keeping their hold in France. The King, however, was convinced that Paris could be regained by peace treaties and negotiations. Joan waited through countless treaty negotiations and court treacheries. When she could stand no more she set out with a company of men to Paris. Joan waited in St. Denis outside Paris for Charles to join them. When Joan had joined the army she had insisted that "cursing, thieving and consorting with loose women" be abandoned. While waiting in St. Denis Joan discovered a group of wenches with the soldiers, as she was driving them off she hit a rock with her sword and the blade snapped in two. The blade could not be repaired, and some saw it as a bad sign. The attack on Paris did not go well and the French were forced to retreat. The rumors began that the Maid had lost her power.

Joan waited as Charles moved to Bourges to take up the courtly life Joanís battles had taken him from. La Hire said to Charles, "I have never seen a prince lose his estates so gaily." When a truce between Charles and the Burgundians finally expired Joan was once again given her chance to defend her country and rid it of the English. This time the target was Compiengne, often know as the "Gateway to the North."

In the battle that occurred outside the city the French troops were thrown into confession, many retreated back into the safety of the city wall and pulled the draw bridge up behind them. This left Joan outside with handful of men forced to defend themselves as best they could. One by one the vastly out numbered Frenchmen fell . The remaining few fought to protect the Maid. As her squire fell in a last attempt to save her, an enemy archer dragged her from her horse and demanded that she surrender. She refused, until an English Officer came forward declaring himself of noble blood and she surrendered to him. She was bond and taken to Margny.

The next question for the English was what to do with Joan the Maid, the English could not simply kill her, for that would make her a martyr and the French might be inspired to rise up in her memory. They had to prove that she was not the "Messenger of God," to show the French people that she was not worth following.

While the English struggled to find a way to get rid of her, many of Franceís people cried and prayed for Joan to be set free. They raised money, willing to pay any ransom for the maid who had brought hope back into their lives. But Charles did nothing; she had crowned him and restored his kingdom, and still he did nothing.

Joan was taken to Roun where she was put on trial by the church, accused of heresy. Her chief judge was Pierre Cauchon, under the pay of the English crown and a bitter enemy of Charles.

Joan was asked questions meant to confuse her into saying she was indeed a heretic. When asked "Do you know whether you are in Godís grace?" As a Christian she could not answer "yes" for she could not know for certain. If she answered "no" they would condemn her of heresy. So the illiterate young maid from Domremy answers in simple truth and eloquence, "If I am not in Godís grace, I pray God to put me there; if I am, may God keep me there." When they could not trick her with words, they tried torture. Her judges threatened her with fire. They read a list of charges condemning her of heresy and witchcraft. In an attempt to infuriate Joan, Guillaume Erard, cried out, "Your King is a heretic!" Joan interrupted as calm and eloquent as she had in her trial, "With all due respect to you, I swear that my King is the most noble Christian of all Christians."

The priests began to chant, "submit to the Church," the crowd joined in and the square became filled with the deafening cry. Joan looked over and saw the executioner waiting, in a moment of fear she cried out, "I submit to the judgment of the Church." In this brief sentence, she had denied that her voices existed and the English had won.

Joan was returned to her cell and over the next three days she was terrified worse than before. She put back on her menís clothes, and tore up the submission she had signed. She told Cauchon that, "My voices have told me...that I did wrong in recanting and that I must confess that I did wrong. It was fear of the fire that made me say that which I said..."

As Cauchon left Joanís cell he ran into an English noblemen and said, "Farewell. Be of good cheer, she is yours now." The English now had enough proof to condemn her of heresy.

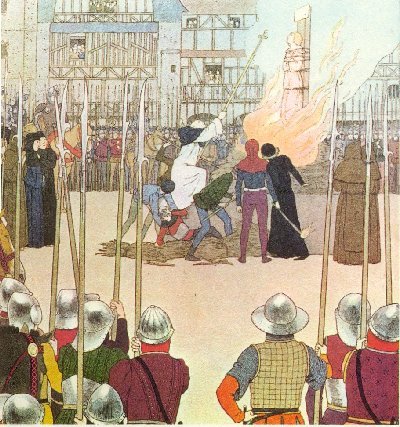

On Wednesday morning, May 30, 1431, Joan the Maid, at age nineteen, was taken from her cell and led to the public square. She was placed on a platform across from where her judges sat. They read to her for nearly an hour from her final sentence. She was then handed over to the secular authorities, for the Church could not carry out executions. Joan began to weep and pray aloud, she implored the crowd "to forgive the harm I have done you as I forgive the harm you have done men." Joan was placed on top of pile of wood and tied to the stake, she asked for a crucifix to held before her eyes until she died. While a priest ran to the Church to get one an English soldier moved by Joanís plight tied two twigs together and gave them to Joan. As the fire was set the priest returned with the cross, he held it up before her eyes as the flames licked her feet. Joanís voice could be heard crying to her saints and God in one final breath she cried out "Jesus, Jesus"

Joan being burned at the stake

Her ashes were gathered and thrown into the dirty water of the Seine River, the witch was dead, the maid who had given hope to France, who had crowned their King and restored their county, was dead. Many French wept and even some of the English cried, "We are all damned; we have burned a saint."

Within 30 years of Joanís death, the French, united in her memory, drove the English out of France and the French nation was born.

Brooks, Polly Schoyer. Beyond the Myth the Story of Joan of Arc. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1990

Dana, Barbara. Young Joan. New York: Harper Collins, 1991

Shaw, Bernard. Saint Joan. New York: Penguin Books, 1924

Twain, Mark. Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc. New York: Random House Value Publishing, Inc.1995

Williams, Jay. Joan of Arc. New York: American Heritage Publishing Co., Inc, 1963

Picture #1 - "Joan as a soldier" from: Joan of Arc

Picture #2 - "only picture of Joan..." from: Beyond the Myth The Story of Joan of Arc

Picture #3 - "Map of Joan's France" from: Joan of Arc

Picture #4 - "Joanís coat of arms" from: Joan of Arc

Picture #5 - "Joan being burned at the stake" from: Joan of Arc